Private refugee camp in Al Ramtha, on the Syrian border. When I returned to the Syrian refugees this September there was still misery, sadness and fear. But I also experienced something new. Here's what I wrote about that.

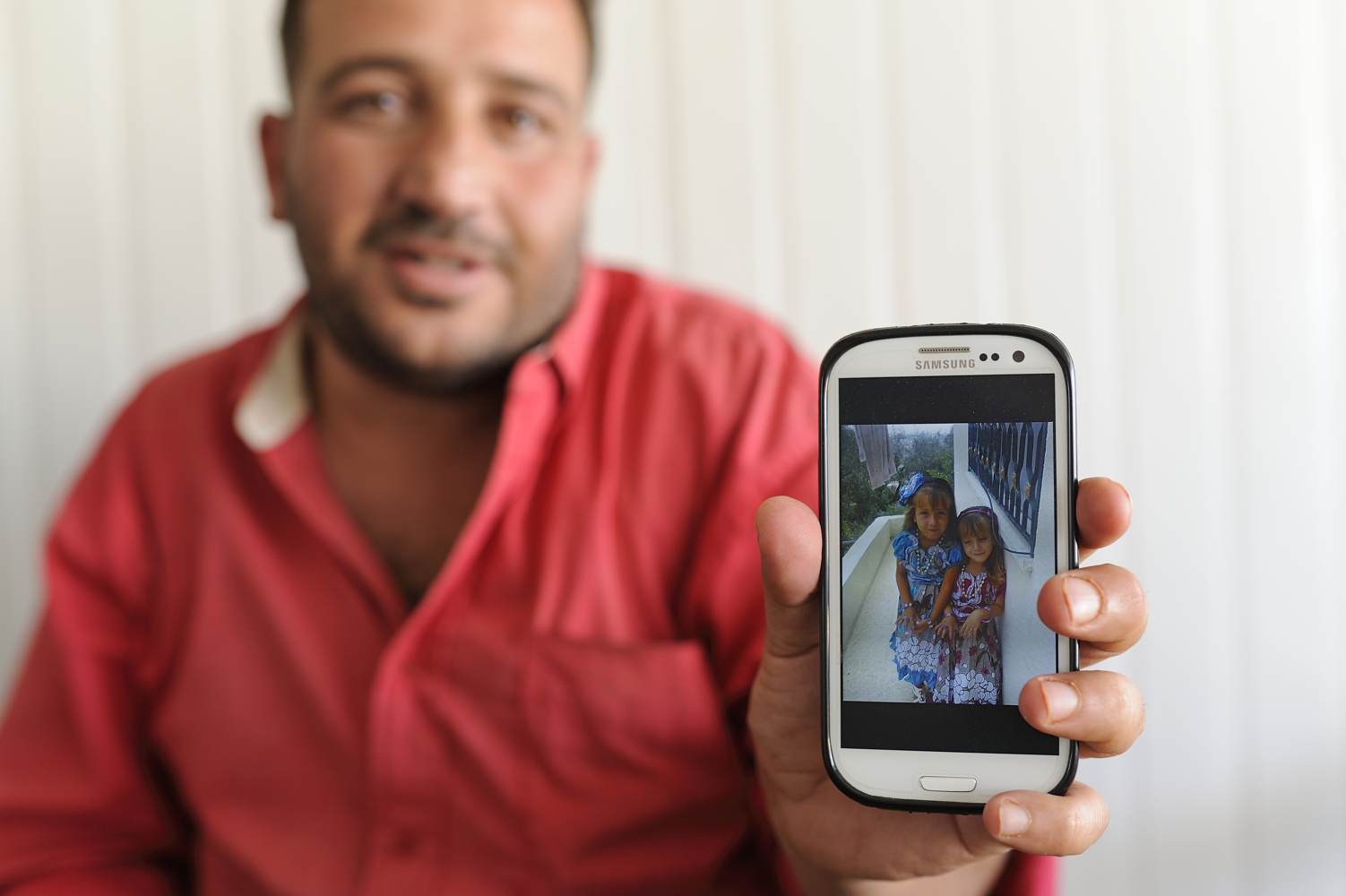

A father who lost 4 children during a bombardment shows an image of his two daughters.

Sitting room in the private refugee camp in Al Ramtha.

Syrian kids in Al Ramtha, Jordan.

Za'atari refugee camp is now open for more than two years and it is touching to see how people are trying to restore normal life again. This biology teacher told me how happy he was that he could have a few singing birds in his house again.

Abu Mohammed's restaurant was the first in Za'atari and became famous all over the world because hundreds of journalists visited the place.

Most refugees in Za'atari now live in caravans; many have also organised concrete floors themselves.

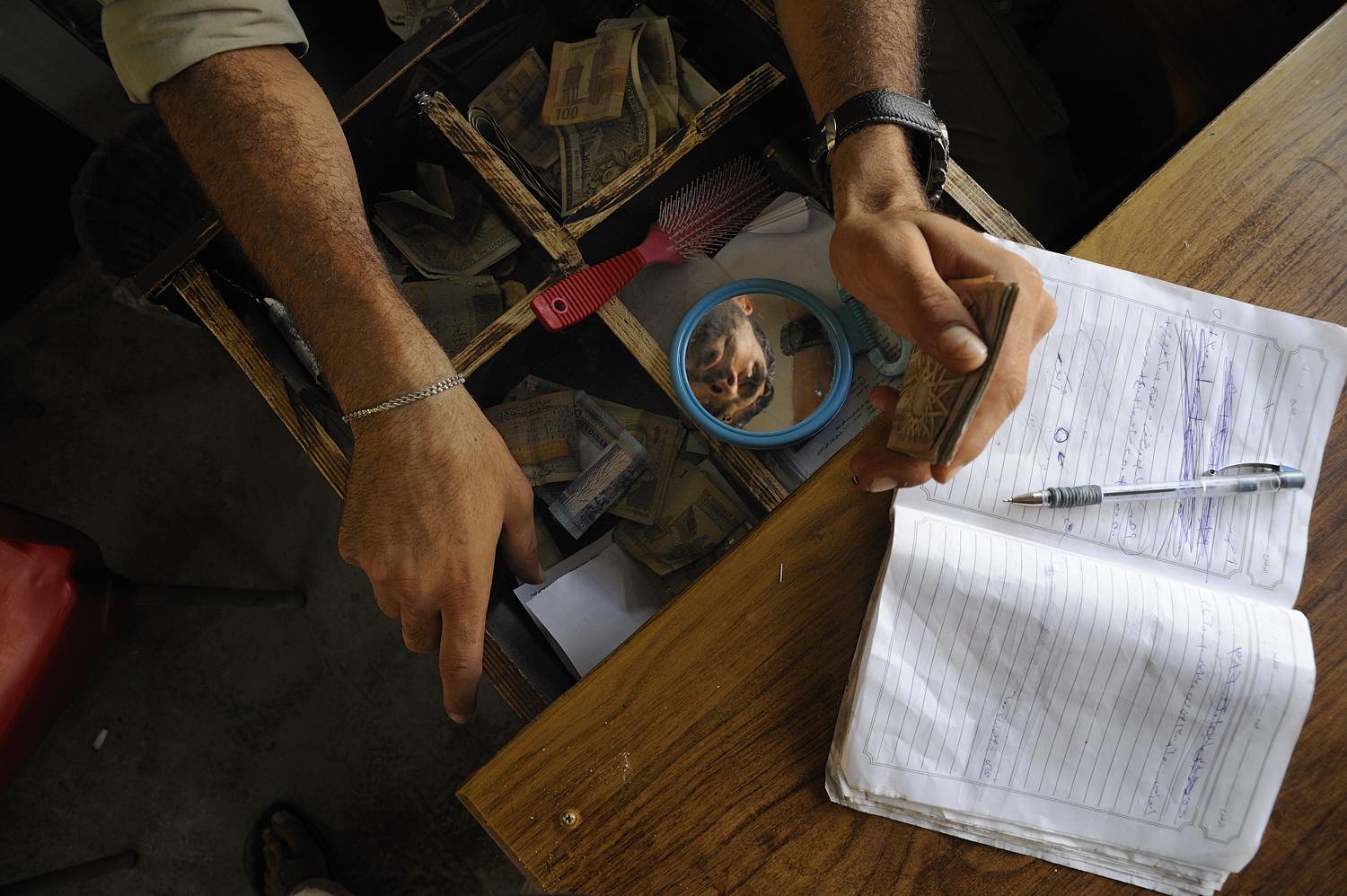

There are no banks or ATM's in the refugee camp, but plenty of money changers.

Prayers in Za' atari refugee camp. The camp is now bustling with economic activity.

Cigarette stall in Za'atari's main street, nicknamed Champs Elysees.

Refugees that succeed in finding a place outside the camp are - in general - much better of and enjoy a lot more freedom, like this Syrian family in Umm al Jimal.

Bread is distributed daily by the UNHCR in Za'atari camp; yet the Syrians prefer their own fresh bread.

The owner of a barbershop shows the scissors and the razor he could take with him when he fled Syria.

Just opened on Za' atari's Champs Elysees: the jeweller's shop.

The daily water trucks bring some distraction in the camp. But it is a dangerous game, and a few children have already been killed.

Tapping electricity illegally is still an issue in the camp.

Boys are having fun in the dirty water that leaks from one of the three bore holes in the camp.

Last year everybody was talking about going back. Now people are trying to make their lives here more comfortable; many of them have installed private toilets with black water tanks underground.

Most refugees in Za'atari are farmers from nearby Dara'a in Syria. More and more people are now trying to grow their own crops in the camp.

Interior of a little coffeeshop in Za'atari.

A barbershop on the Champs Elysees.

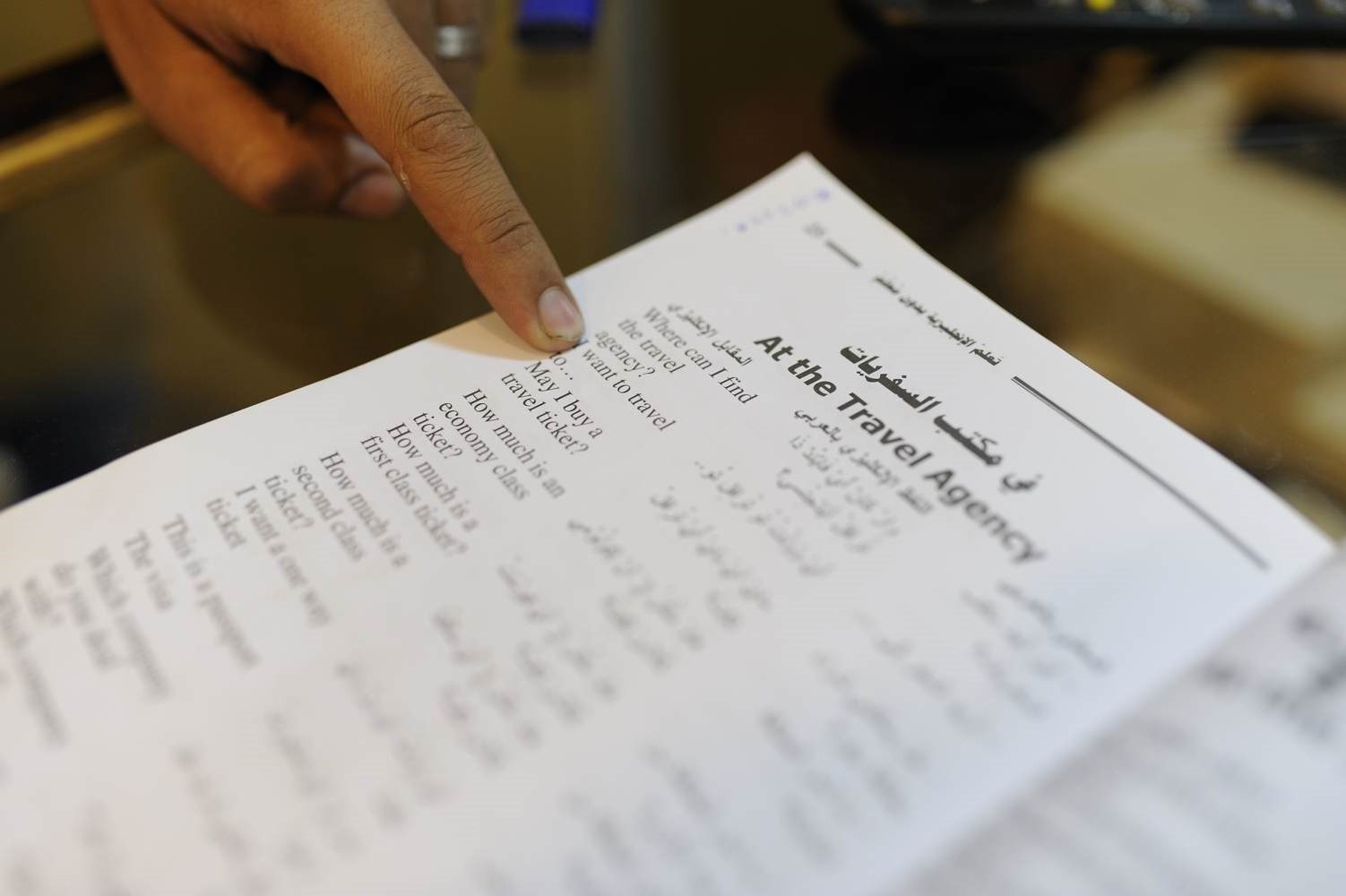

Most conversations with refugees in the camp sooner or later move to the subject: how can I get to your country?

Ten year old Rafran was badly burnt on the right side of her body when her family's house in Aleppo caught fire in February 2012. 'My mother was feeding the baby and fell asleep. When she woke up, the whole house was on fire already.' The fire started because the family had to use kerosine lamps due to a power cut that had already lasted for days. Rafran's mother and baby sister also suffered severe burns.

Shortly after this disaster the family moved into another house. When that was destroyed during a bombardment they fled and crossed the border into Jordan. They are now living in Mafraq. Rafran says she can still hear the sounds of the war, every single day. 'I am still scared'.

The scars of her burns did bother at first, but no more: 'I have accepted it.'

Every day between 10 and 12 children are born in Zaatari. French Gynecologist sans Frontrieres operate a clinic to assist with pregnancies. But in the camp itself the living conditions for both parents and children are still very basic and sometimes unhygienic.

Amar (4) in front of the garage that she lives in together with her parents, grandmother, little brother and sister. Amar's father found a job picking fruit in Mafraq and is away all day.

Her mother has a hard time raising the children here, and she's expecting another child. 'This is not the place to raise a family. The kids are bored and getting more aggressive every day. But what can I do?'

Dutch church volunteer Jan Willem Petersen (27) plays with 2 year old Rahami during a visit to a family that found refuge in a garage in Mafraq's outskirts. Rahami's family pays 120 Jordanian Dinar (appr. 150 $) per month for this place. A year ago the price would have been only 20 JD.

Rahami's mother Fatma sometimes has to sell her UNHCR food coupons to be able to pay the rent. 'That means we are hungry sometimes. But that's just the way it is. Things will get better sooner or later, Insha'allah. At least we are safe here.'

7 months ago the family was escorted from Aleppo to the border by two fighters from the Free Syrian Army. Just before reaching the border these men were shot and killed in their presence.

Fatma is pregnant from her 4th child and will deliver within 4 months. She hopes that by then she can get access to a hospital.

A refugee shows an image of Syrian leader Assad (or 'Bashar' as they call him here) dressed as a woman, expressing his hate towards the Syrian dictator.

Things go fast in Zaatari refugee camp. When the camp opened a little over 1,5 years ago people were completely dependent on aid. Now there is an estimated 3.000 shops in this huge camp, varying from this tv-store to the mother of a family selling some sweets in front of her tent.

Zaatari has restaurants, coffee shops, icecream parlours, hairdressers and of course lots of shops selling phones and phone cards. Most of the shops are concentrated on the main street, renamed 'Champs Elysees' by the French hospital located at the entrance of the camp. The residents of Al-Za'atari call it their 'Main Street' or 'Shopping street'.

A volunteer from the Christian & Missionary Alliance Church in Mafraq digs through piles of cushions and sheets stashed in a warehouse to distribute to newly arrived refugees.

The local church supports 400 of the 5000 Syrian families that live in Mafraq, and visits them personally every once in a while. Mafraq probably houses about 35.000 refugees by now, but up until this day the big NGO’s seem to focus completely on the Za’atari refugee camp 10 kilometers out of town. UNHCR considers setting up an Urban Refugee Program and plans to open an office in Mafraq within a month.

Zaatari's inhabitants take care of themselves a bit more every day, but bread is one of the things they need from the outside. Every day half a million pieces of bread are being distributed amongst the 116.000 inhabitants of the camp.

Jordan has a long history of heavily subsidizing bread, making it so cheap that there's hardly any chance that the Syrian's themselves will find a way to make the bread business worthwhile.

Theft is a major problem in Zaatari. Sanitary blocks like this one can simply disappear overnight. The people are constantly on the lookout for things they can use to make their own quarters a little bit more comfortable.

As soon as refugees started arriving in Zaatari, they started siphoning of electricity from the main power cables. During the cold winters heating is essential; in summer months temperatures rise above 40 degrees and living without a ventilator is almost impossible.

By now you will find hundreds of kilometres of wiring all over the camp, sometimes dug in, sometimes just open on te ground where children play. In summer this is not causing too much danger, but Zaatari's inhabitants realise things could turn nasty when the rains set in this autumn..

This boy is helping his father with the wiring from their tent all the way to the main cable. To connect the wire to the cable, they have to hire somebody that will do the dangerous and illegal job at night.

The UNHCR is working on plans to get the electricity business better organised, with metering and prepaid cards. That could make things safer and it will eliminate the local maffia that now controls parts of this business.

A shopowner in Za'atari refugee camp show an image of a friend who was killed in the war

This man is another example of succesfull enterpreneurship; his restaurant has its own water supply, meaning that customers can even wash their hands before and after their meals.

Every day a 100 chicken are being grilled and served here; the quality of the food is so good that he even gets some of the more courageous UNHCR staff in as his customers.

Building material is very hard to get, so people have to be very inventive. The desk imaged here is built from wood panels meant for flooring.

The first private garage in Zaatari popped up this week. The fencing was stolen from somewhere else in the camp.

Za’atari houses approximately 60.000 children, of which only about 4.000 - 5.000 attend the schools that offer room for 10.000 students. Many refugees are from illiterate areas. They either need their children to help generating some income, or let them assist with daily tasks like picking up the bread at the distribution centre of the World Food Program.

Every morning there are hundreds of kids carrying the bread to their tents and caravans. Some swap a piece of bread for a cup of sweet candycream, some of them are hungry and start eating the bread as soon as they get it.

The influx of refugees is a volatile and uncontrollable thing. During the worst moments more than 3.000 people arrived every single day. By now between 50 and 200 people arrive daily. But many residents also leave to either Mafraq, another city, or back into Syria.

This old man arrived late at night together with a group of 50 refugees. Now that things are not as hectic any more, reception of the people has become a bit more civilised; with water and tea waiting for them.

Business are thriving in Zaatari's main street or 'Champs Elysees', and people use anything available to build their shops and restaurants.

Windows are hard to get, so this shawarma restaurant uses thick plastic instead.

The sleepy provincial town of Mafraq doubled in size since the influx of refugees. Local businesses are flourishing.